Chapter 2: Energy Audits and Quality Control Inspections

This chapter outlines the operational process of energy audits, work orders, and final inspections as practiced by non-profit agencies and contractors working in the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP).

WAP’s Mission

The mission of DOE WAP is “To reduce energy costs for low-income families, particularly for the elderly, people with disabilities, and children, by improving the energy efficiency of their homes while ensuring their health and safety.”

This chapter also discusses ethics, client relations, and client education.

Applicable DOE Policy

Comply with DOE Policy as expressed by Weatherization Program Notices (WPNs) and memorandums that DOE issues several times each program year. See DOE's EERE Guidance Page

Also comply with the DOE’s Standard Work Specifications (SWS) for all energy conservation measures that your weatherization service provider installs. This field guide links to the SWS through a data-base tool managed by the National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL).

Why We Care about Health and Safety

The health and safety of clients must never be compromised by weatherization. Harm caused by our work would hurt our clients, ourselves, and our profession. Weatherization work can change the operation of heating and cooling systems, alter the moisture balance within the home, and reduce a home’s natural ventilation rate. Weatherization workers must take all necessary precautions to avoid harm from these changes.

2.1 Purposes of an Energy Audit

An energy audit evaluates a home’s existing condition and outlines improvements to the energy efficiency, health, safety, and durability of the home.

Depending on the level of the audit, an energy audit may include some or all of the following tasks.

• Inspect the building and its mechanical systems to gather the information necessary for decision-making.

• Evaluate the current energy consumption along with the existing condition of the building.

• Diagnose areas of energy waste, health and safety, and durability problems related to energy conservation.

• Recommend energy conservation measures (ECMs).

• Diagnose health and safety problems, and how the proposed ECMs may affect these problems.

• Estimate labor and material costs for ECMs.

• Educate residents about their energy usage and proposed energy retrofits.

• Encourage behavioral changes that reduce energy waste.

• Create written documentation of the energy audit and the recommendations offered.

2.1.1 Energy-Auditing Judgment and Ethics

The auditor’s good decisions are essential to the success of a weatherization program. Good decisions depend on judgment and ethics.

✓ Understand the policy of the DOE WAP program.

✓ Treat every client with the same high level of respect.

✓ Communicate honestly with clients, coworkers, contractors, and supervisors.

✓ Know the limits of your authority, and ask for guidance when you need it.

✓ Develop and maintain the inspection, diagnosis, and software skills necessary for WAP energy auditing.

✓ Choose ECMs according to their cost-effectiveness along with DOE and State policy, and not according to personal preference or client preference.

✓ Don’t manipulate the energy-modeling software to either select or avoid particular ECMs.

✓ Avoid personal bias in your influence on purchasing, hiring, and contracting.

2.1.2 Health and Safety Considerations

Energy auditors and inspectors must know and understand the health and safety (H&S) policies of the State weatherization program. H&S measures impact the budget and the economic viability of most weatherization jobs. An auditor may justify a H&S measures as any of the following types according to current H&S WPNs and CSPM 614.

1. A required H&S measure funded by the State’s H&S budget, which protects occupants or workers but isn’t justified by the energy audit and isn’t included in the average cost per unit (ACPU).

2. An incidental repair measure (IRM), with H&S benefits, funded to protect an ECM or to mitigate a relatively inexpensive hazard such as a roof leak, chimney repair, or electrical repair.

3. A H&S measure that serves as a precaution or a benefit of a cost-effective ECM, and in this case, the H&S measure adds costs to the SIR calculation.

4. A H&S benefit of an ECM that isn’t itself cost-effective but justifiable by the H&S benefits combined with the ECM’s energy savings.

When you consider whether a measure is an ECM for H&S, evaluate its SIR, and if cost-effective, treat it as an ECM.

2.1.3 Energy-Auditing Record-keeping

The client file is the record of a weatherization job. See CSPM 612 for the minimum contents required in the completed client file.

Client satisfaction depends on the energy auditor’s reputation, professional courtesy, and ability to communicate.

2.2.1 Communication Best Practices

Making a good first impression is important for client relations. Friendly, honest, and straightforward communication creates an atmosphere where the auditor and clients can discuss problems and solutions openly.

Setting priorities for client communication is important for the efficient use of your time. Auditors must communicate clearly and directly. Limit your communication with the client to the most important energy, health, safety, and durability issues.

✓ Introduce yourself, identify your agency, and explain the purpose of your visit.

✓ Make sure that the client understands the goals of the WAP program.

✓ Listen carefully to your client’s reports, complaints, questions, and ideas about their home’s energy efficiency.

✓ Ask questions to clarify your understanding of your client’s concerns.

✓ Before you leave, give the client a quick summary of what you found.

✓ Avoid making promises related to the scope of work, until you have time to finish the audit, produce a work order, and schedule the work.

✓ Make arrangements for additional visits by crews and contractors as appropriate.

The client interview is an important part of the energy audit. Even if clients have little understanding of energy usage and building science, they can provide useful observations that can save you time and help you choose the right ECMs.

✓ Ask the client about comfort problems, including rooms that are too cold or too warm.

✓ Ask clients to see their energy bills if you haven’t already evaluated them.

✓ Ask clients if there is anything relevant they notice about the performance of their mechanical equipment.

✓ Ask about family health, especially respiratory problems afflicting one or more family members.

✓ Discuss space heaters, fireplaces, attached garages, and other combustion hazards.

✓ Notify the client of any necessary measures that will change the appearance, noise level, or operation of the dwelling.

✓ Discuss drainage issues, wet basements or crawl spaces, leaky plumbing, and pest infestations.

✓ Discuss the home’s existing condition and how the home may change after the proposed retrofits.

✓ Identify existing damage to finishes to ensure that weatherization workers aren’t blamed for existing damage. Document damage with digital photos.

✓ Ask the client to sign the necessary permissions.

2.2.3 Deferral of Weatherization Services

When you find major health, safety, or durability problems in a home, sometimes it’s necessary to postpone weatherization services until those problems are solved. The problems that are cause for deferral of services include but are not limited to the following. Each agency must create a deferral policy. See CSPM 609 for more complete guidance.

• Major roof leakage or major foundation damage.

• Major moisture problems including mold or insect infestation.

• Major plumbing problems.

• Human or animal waste in the home.

• Major electrical problems or fire hazards.

• The home is for sale, vacant, or the client is moving.

• Client refusal of a cost-justified major measure.

• Client refusal of a necessary health and safety measure.

Client behavioral problems may also be a reason to defer services, including but not limited to the following.

• Illegal activity on the premises. (This includes marijuana)

• Occupant’s hoarding makes it difficult or impossible to perform a complete audit.

• Lack of cooperation by the client.

Matching Funds to Avoid Deferrals

Energy auditors should assist clients in obtaining repair funds from the following sources whenever possible.

• HUD HOME Rehabilitation Funds for Homeowners

• USDA Rural Development Housing Repair Funds

• Habitat for Humanity Home Preservation

• State and local repair funds

• Church, charity, and foundation funds

Visual inspection, diagnostic testing, and numerical analysis are three types of energy auditing procedures we discuss in this section. These procedures help energy auditors to evaluate all the possible ECMs that are cost-effective according to DOE-approved energy-modeling software: Weatherization Assistant or approved equivalent. See “Quantitative Analysis: Software” on page 79.

To understand the features of Weatherization Assistant, consult the DOE Weatherization Assistant training site.

The energy audit must also propose solutions to health and safety problems related to the energy conservation measures.

Visual inspection orients the energy auditor to the physical realities of the home and home site. Among the areas of inspection are these.

• Health and safety issues

• Building air leakage

• Building insulation and thermal resistance

• Heating and cooling systems

• Ventilation fans and operable windows

• Baseload energy uses

• The home’s physical dimensions: area and volume

Measurement instruments provide important information about a building’s unknowns, such as air leakage and operational characteristics of combustion appliances. Use these diagnostic tests as appropriate during the energy audit.

• Blower door testing: A variety of procedures used to evaluate the airtightness of a home and to determine the location of its air barriers. Zone Pressure Diagnostics (ZPD) for attics, attached garages, and other appropriate zones are included.

• Duct leakage testing: A variety of tests used to evaluate duct leakage; typically done using a blower door and pressure pan or a duct pressurization device.

• Room pressures testing: Taken during air handler operation.

• Ventilation testing: Measure airflow through existing exhaust fans with an exhaust-fan flow meter.

• Combustion Appliance Zone (CAZ) testing: Sample combustion by-products and measure depressurization to evaluate safety and efficiency. Test the home’s ambient air for CO.

• Test gas systems for fuel leaks with a combustible gas detector.

• Infrared scanning: View building components through an infrared scanner to observe differences in the temperature of building components inside building cavities.

• Appliance consumption testing: Monitor refrigerators with a logging watt-hour meter to measure electricity consumption.

2.3.3 Quantitative Analysis: Software

All Michigan Subgrantees will use the NEAT/MHEA audit tools for single family residential energy audits. Only DOE approved audit tools will be used for multi-family dwelling units.

Proper use of this software will determine a list of Energy Conservation Measures (ECMs) for a building based on a savings to investment ratio (SIR). The savings over the lifetime of the measure, discounted to present value, must typically meet or exceed the total cost of implementing the measure.

SIR = LIFETIME SAVINGS ÷ INITIAL INVESTMENT

Auditors must collect all the necessary building information and diagnostic test results in order to complete the audit file and obtain an SIR driven work order. See CSPM 600 Series for more comprehensive program requirement guidance.

The work order is a list of materials and tasks that are recommended as a result of an energy audit. Consider these steps in developing the work order.

✓ Evaluate which ECMs have an acceptable savings-to-investment ratio (SIR) using the energy-modeling software.

✓ Provide detailed ECM specifications so that crews or contractors clearly understand the materials and procedures necessary to complete the job.

✓ Estimate the cost of the materials and labor.

✓ Address all relevant health and safety issues.

✓ Inform crews or contractors of any hazards, pending repairs, and important procedures related to their part of the work order.

✓ Obtain required permits from the local building jurisdiction, if necessary.

✓ Specify interim testing during air-sealing and heating-system maintenance to provide feedback for workers.

✓ Consider scheduling an in-progress inspection.

✓ Consider scheduling a final inspection for the job’s final day.

2.5 Quality Control Inspections

The quality-control inspector (QCI) is responsible for the quality control and quality assurance of the weatherization process. Good inspections provide quality control for both work orders and energy audits. There are two common opportunities for inspections: in-progress inspections and final inspections.

DOE encourages QCIs and Energy Auditors to inspect jobs while the job is in progress. In-progress inspections evaluate worker safety, observe ongoing procedures to ensure work meets required standards, and can provide training, technical assistance, and occupant education.

These measures are good candidates for in-progress inspections because of the difficulty of evaluating them after completion.

• Dense-pack wall insulation

• Attic air sealing

• Insulating closed roof cavities

• Furnace installation or tune-up

• Air-conditioning service

• Duct testing and sealing

• Lead-safe work practices

2.5.2 Subgrantee Final Inspections

The weatherization service provider or Subgrantee does final inspections on all of its weatherized homes for quality control. Quality control is a term for the in-house self-evaluation of weatherization jobs. A certified QCI completes a final inspection before the Subgrantee reports a weatherization job as a completion to the Grantee.

Final inspections ensure that the energy auditor identified the right ECMs, and that the crew and contractors installed the ECMs as specified in the work order and that the work meets required standards.

Final inspections must include the following elements:

✓ Verify worker compliance with safety regulations.

✓ Evaluate in-process work quality.

✓ Verify on-site documentation.

✓ Verify installed measures and initial assessment details.

✓ Evaluate installed measures for compliance with standards.

✓ Confirm whether policy requirements have been satisfied.

✓ Confirm there were no missed opportunities.

2.6 Understanding Energy Usage

A major purpose of any energy audit is to determine where energy waste occurs. With this information in hand, the energy auditor then allocates resources according to the energy-savings potential of each energy-conservation measure. A solid understanding of how homes use energy should guide the decision-making process.

|

Energy User |

Annual kWh |

Annual Therms |

|---|---|---|

|

Heating |

2000–10,000 |

200–1100 |

|

Cooling |

600–7000 |

n/a |

|

Water Heating |

2000–7000 |

150–450 |

|

Refrigerator |

500–2500 |

n/a |

|

Lighting |

500–2000 |

n/a |

|

Clothes Dryer |

500–1500 |

n/a |

|

Estimates by the authors from a variety of sources. |

||

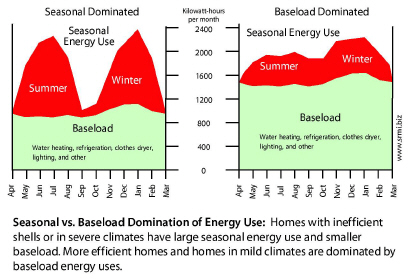

2.6.1 Baseload Versus Seasonal Use

We divide home energy usage into two categories: baseload and seasonal. Baseload includes water heating, lighting, refrigerator, and other appliances used year round. Seasonal energy use includes heating and cooling. You should understand which of the two is dominant as well as which types of baseloads and seasonal loads are the highest energy consumers.

Many homes are supplied with both electricity and at least one source of combustion fuel. Electricity can provide all seasonal and baseload energy, however most often there is a combination of electricity and natural gas, oil, or propane. The auditor must understand whether loads like the heating system, clothes dryer, water heater, and kitchen range are serviced by electricity or by fossil fuel.

Total energy use relates directly to potential energy savings. The greatest savings are possible in homes with highest initial consumption. Avoid getting too focused on a single energy-waste category. Consider all the individual energy users that offer measurable energy savings.

Separating Baseload and Seasonal Energy Uses

To separate baseload from seasonal energy consumption for a home with monthly gas and electric billing, do these steps.

1. Get the energy billing for one full year. If the client can’t produce these bills, they can usually request a summary from their utility company.

2. Add the 3 lowest bills together.

3. Divide that total by 3.

4. Multiply this three-month low-bill average by 12. This is the approximate annual baseload energy cost.

5. Total all 12 monthly billings.

6. Subtract the annual baseload cost from the total billings. This remainder is the space heating and cooling cost.

7. Heating is separated from cooling by looking at the months where the energy is used — summer for cooling, winter for heating.

8. For cold climates, add 5 to 15 percent to the baseload energy before subtracting it from the total to account for more hot water and lighting being used during the winter months.

Energy indexes are useful for comparing homes and characterizing their energy efficiency. They are used to measure the opportunity for application of weatherization or home performance work.

Most indexes are based on the square footage of conditioned floor space. The simplest indexes divide a home’s energy use in either kilowatt-hours or British thermal units (BTUs) by the square footage of floor space.

A more complex index compares heating energy use with the climate’s severity. BTUs of heating energy are divided by both square feet and heating degree days to calculate this index.

Client education is a valuable tool designed to encourage client participation in all aspects of the Weatherization process. Working as partners, weatherization practitioners and clients enhance the energy savings and efficiency of every home receiving weatherization services. A well designed and implemented client education program ensures the client understands how their home functions, steps they can take to increase energy savings, and their responsibility to maintain the installed energy conservation measures

Clients should be provided with no-cost to low-cost energy saving tips including, but not limited to: proper thermostat operation, adjusting of water temperature, maintenance of HVAC equipment, turning off unused lights, house preparation for winter months, and unplugging unused electronics.