Install wall-cavity insulation with a uniform coverage and density. Wall cavities encourage airflow like chimneys. Convection currents or air leakage can significantly reduce wall insulation’s thermal performance if channels remain for air to migrate or convect.

Blown Wall-Insulation Types

Cellulose, fiberglass, and open-cell polyurethane foam are the leading insulation products for retrofit-installation into walls.

|

Insulation Material |

Density |

R-Value/in. |

|---|---|---|

|

2.2 pcf |

4.1 |

|

|

Cellulose |

3.5 pcf |

3.4 |

|

Open-cell urethane foam |

0.5 pcf |

3.8 |

|

pcf = pounds per cubic foot |

||

5.3.1 Wall Insulation: Preparation and Follow-up

Inspect and repair walls thoroughly to avoid damaging the walls, blowing insulation into unwanted areas, or causing a dust hazard.

Preparing for Wall Insulation

Before starting to blow insulation into walls, take the following preparatory steps.

ü Calculate how many bags of insulation are needed to achieve the R-value specified on the bag’s label.

ü Inspect walls for evidence of moisture damage. If an inspection of the siding, sheathing, or interior wall finish shows a moisture problem, don’t install sidewall insulation until the moisture problem is identified and solved.

ü Inspect indoor surfaces of exterior walls to assure that they are strong enough to withstand the force of insulation blowing. Reinforce interior sheeting as necessary.

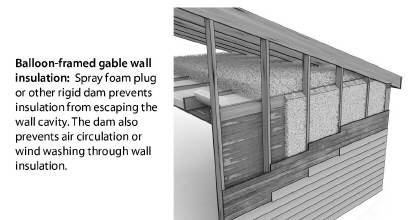

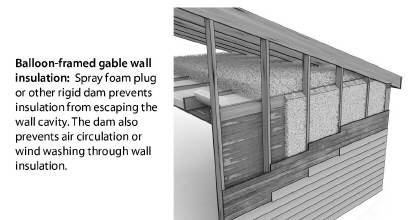

ü Inspect for interior openings or cavities through which insulation may escape. Examples include balloon-framing openings in the attic or crawl space, pocket doors, un-backed cabinets, interior soffits, and openings around pipes under sinks, and closets. Seal these openings to prevent insulation from escaping the wall cavity.

ü Verify that exterior wall cavities aren’t used as return or supply ducts. Either avoid insulating these cavities, or re-move the ducts and reinstall them somewhere else.

ü Verify that electrical circuits inside the walls aren’t overloaded. Maximum ampacity for 14-gauge copper wire is 15 amps and for 12-gauge copper wire is 20 amps. Install S-type fuses to prevent circuit overloading if necessary. Don’t insulate cavities containing knob-and-tube wiring. See “Electrical Safety” on page 42.

Patching and Finish after Insulating

The insulators, the home owner, and others should agree about the patching method and the final appearance of the wall finish. The insulators are usually responsible for patching holes and returning the interior or exterior finish to its previous condition or some pre-agreed level of finish.

ü Patch the exterior wall sheathing with wood plugs, plastic plugs, or spray foam insulation.

ü Use caulk or putty and primer to dress exposed exterior plugs.

ü Seal gaps in external window trim and other areas that may admit rain water into the wall.

ü Patch interior finish with standard plastering methods or a chair rail trim board.

ü Install drywall with joint compound to open cavities to comply with IRC fire codes.

Wall Insulation Quality Control

Retrofit wall insulation has more risk of incomplete application than insulation that you can visually inspect. Consider these quality control options to verify the proper coverage and density of retrofit wall insulation.

• Viewing the wall through an infrared camera.

• Looking through an electrical outlet or other access hole for insulation.

• Calculation of installed weight of installed insulation compared to wall-cavity volume and required density.

Drilling Exterior Sheathing: Insulation Retrofit

Avoid drilling through siding. Where possible, carefully remove siding and drill through sheathing. This procedure avoids the potential lead-paint hazard of drilling the siding. Drilling through only the sheathing also makes it easier to insert flexible fill tubes since the holes pass through only one layer of material.

If you can’t remove the siding, consider drilling the walls from inside the home. Obtain the owner’s permission before drilling indoors, and practice lead-safe weatherization procedures. See page 52.

Consider these possible methods of removing siding.

• Cut completely through the paint on wood-siding joints with a sharp utility knife before carefully prying the siding off.

• Remove asbestos shingles by pulling the nails holding the shingles to the sheathing, or else cut off the nail heads. Dampen the asbestos tiles to reduce dust. Wear a respirator and coveralls when working with asbestos siding.

• Use a zip tool to remove metal or vinyl siding.

• Insulate homes with brick veneer or blind-nailed asbestos siding from the indoors.

• Use a decorative chair rail to cover holes drilled indoors.

Restore holes drilled for insulation to an appearance as close to original as possible, or in a manner that is satisfactory to the customer.

5.3.2 Retrofit Closed-Cavity Wall Insulation

|

SWS Detail: 4.1103.1 Dense Pack Exterior Walls, 4.1103.2 Additional Exterior Wall Cavities |

This section describes seven ways of installing wall insulation.

1. Blowing walls with fibrous insulation using a fill tube from indoors or outdoors.

2. Installing batts in an open wall cavity.

3. Injecting liquid foam into a closed wall cavity.

4. Spraying wet-spray fiberglass or cellulose into an open wall cavity.

5. Spray open-cell or closed-cell foam into an open wall cavity.

6. Blowing fibrous insulation behind netting.

Blowing Walls with a Fill-Tube

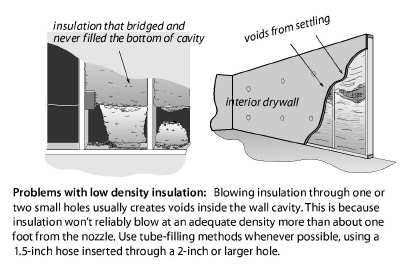

Install dense-pack wall insulation using a blower equipped with separate controls for air and material feed. Mark the fill tube in one-foot intervals to help you verify when the tube reaches the top of the wall cavity.

To prevent settling, cellulose insulation must be blown to at least 3.5 pounds per cubic foot (pcf) density. Fiberglass dense-pack must be 2.2 pcf and the fiberglass material must be designed for dense-pack installation.

Insulate walls using this procedure.

1. Drill 2-to-3-inch diameter holes to access the stud cavity.

2. Probe all wall cavities through holes, before you fill them with the fill tube, to identify fire blocking, diagonal bracing, and other obstacles.

3. Start with several full-height, unobstructed wall cavities so you can measure the insulation density and calibrate the blower. An 8-foot cavity (2-by-4 on 16-inch centers) should consume a minimum of 10 pounds of cellulose or 6 pounds of fiberglass.

4. Insert the hose all the way to the top of the cavity. Start the machine, and back the hose out slowly as the cavity fills.

5. Then fill the bottom of the cavity in the same way.

6. After probing and filling, drill whatever additional holes are necessary for complete coverage. For example: above windows, missed areas with fire blocking.

7. Use the blower’s remote control to achieve a dense pack near the hole while limiting spillage.

8. Seal and plug the holes, repair the weather barrier, and replace the siding.

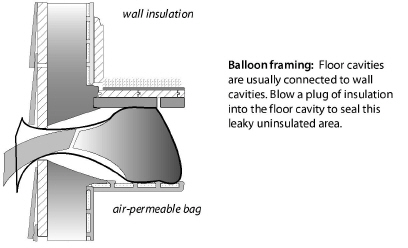

Insulating the Wall-Floor Junction of Balloon-Framed Walls

When insulating the perimeter of balloon-framed walls between the first and second floors, blow an insulation plug into the perimeter floor cavities for both thermal resistance and air-sealing. This insulation plug prevents the floor cavity from being a duct for air migration and leakage. Using a fill tube, blow the insulation into an air-permeable bag that expands inside the cavity. The bag limits the amount of insulation necessary to air-seal and insulate this area.

Injecting Liquid Foam

Injecting liquid foam is more expensive than blowing fibrous insulation but offers better performance when existing walls are partially filled by batts. The batts are often 1-to-2 inches thick and are usually flush with the interior drywall or plaster. Try injecting the foam from outdoors to fill the cavity and compress the batt slightly. From indoors, the foam may just stretch the batt facing and fail to create a fully insulated wall cavity.

Open-cell polyurethane foam, formulated to expand less than the sprayed variety, is the leading wall-retrofit foam. Technicians install the foam through holes (<1 inch) spaced about two feet apart using a simple nozzle that barely enters the cavity. Technicians use drinking straws or other indicators to judge the level that the foam has filled during installation. Technicians don’t normally use fill tubes to inject open-cell foam because the tube would be too difficult to clean.

See “Fire Protection for Foam Insulation” on page 99.

5.3.3 Open-Cavity Wall Insulation

|

SWS Details: 4.1102.1 Open Wall Insulation—General, 4.1102.2 Open Wall—Spray Polyurethane Foam (SPF) Installation |

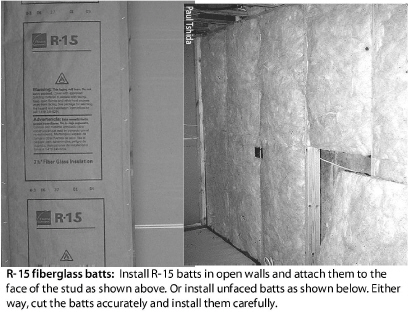

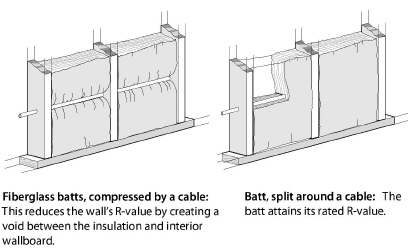

Fiberglass batts are the most common open-cavity wall insulation. Batts achieve their rated R-value only when installed carefully. If there are gaps between the cavity and batt at the top and bottom, the R-value can be reduced by as much as 30 percent. The batt should fill the entire cavity without spaces in corners or edges.

ü Use unfaced friction-fit batt insulation where possible. Fluff the batts during installation to fill the depth of the wall cavity.

ü Choose medium- or high-density batts: R-13 or R-15 rather than R-11, and R-21 rather than R-19.

ü Seal all significant cracks and gaps in the wall structure before or after you install the insulation.

ü Insulate behind and around obstacles with scrap pieces of batt before installing batts.

ü Staple faced insulation to outside face of studs on the warm side of the cavity. Don’t staple the facing to the side of the studs, even though drywallers may prefer that method, because this method leaves an air space that encourages convection currents.

ü Cut batt insulation to the exact length of the cavity. A too-short batt creates air spaces above and beneath the batt, allowing convection. A too-long batt bunches and folds, creating air pockets.

ü Split batt around wiring, rather than letting the wiring compress the batt to one side of the cavity.

ü Fiberglass insulation, exposed to the interior living space, must be covered with minimum half-inch drywall or other material that has an ASTM flame spread rating of 25 or less.

ü Fiberglass batts exposed to unoccupied spaces like attics must be covered with an air barrier such as house wrap or foam sheeting to prevent R-value degradation by convection and human exposure to fibers.

See “Fiberglass Batts and Blankets” on page 92.

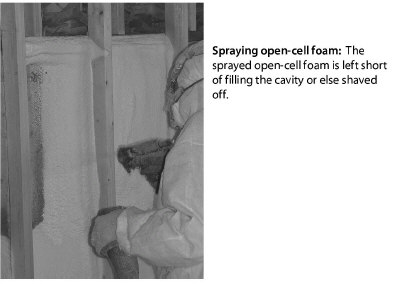

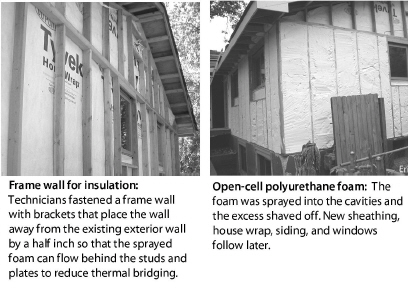

Sprayed Open-Cavity Wall Insulation

Both fibrous and foam insulation can be sprayed into open wall cavities. Varieties include the following.

• Fiberglass or cellulose mixed with water and glue at a special nozzle, and sprayed into the open wall cavity. Then the excess is shaved off (fibrous damp-spray insulation).

• Open-cell or closed-cell polyurethane foam sprayed into an open wall cavity and either held short of filling the whole cavity or with the excess foam shaved off after it cures.

Blowing Open Wall Cavities behind Netting or Fabric

Blowing dry fibrous insulation behind netting or fabric is a common way of insulating open walls before drywall application, especially with cellulose. However, you must install the insulation to a sufficient density to resist settling.

ü Verify density of at least 3.5 pcf for cellulose or 1.6 pcf for fiberglass.

ü Select a restrainer netting or fabric that will allow the above densities without bulging excessively.

ü Fasten the netting or fabric with power-driven staples, 1.5 inches apart.

ü Roll bulging insulation with a roller to facilitate drywall installation.

5.3.4 Insulated Wall Sheathing

|

SWS Detail: 4.1103.3 Insulated Sheathing and Insulated Siding Installation |

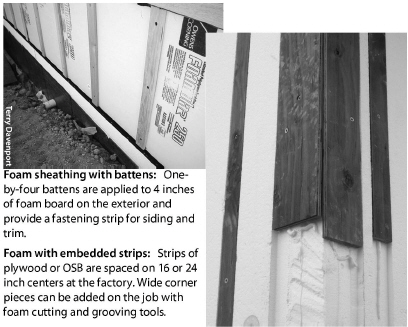

Insulated wall sheathing covers the wall surface with insulation, reducing thermal bridging through structural framing. Insulated sheathing is an excellent retrofit, when you replace the siding and windows.

Insulating wall sheathing is usually foam board, such as polystyrene or polyisocyanurate. Always fill the wall cavity with insulation before installing insulated sheathing.

Fastening Insulating Sheathing

Fastening the insulating sheathing requires one of the following to secure the insulation to the wood sheathing or masonry under it.

• A batten board

• An embedded strip

• A broad staple

• A long screw with a large washer

• A special adhesive (masonry)

Use appropriate fasteners for wood or masonry materials. Wood battens or embedded strips allow attachment of a variety of siding materials. The embedded strips work best with steel, aluminum, or vinyl siding, which are lightweight and drain water through weep holes in every unit of siding.

5.3.5 Wall Insulation in a Retrofitted Frame Wall

Retrofitters, seeking superior energy performance, sometimes build a wood-frame wall attached to the interior or exterior of the existing wall. Common insulation choices include all the wall-insulation choices discussed previously. Vapor retarders and air barriers must be incorporated into the new wall assembly as appropriate for the climate and existing wall characteristics. The exterior side of a retrofitted insulated frame should have sheathing and a water resistive barrier like house wrap.

5.3.6 Insulating Unreinforced Brick Walls

|

SWS Detail: 4.1103.3 Insulated Sheathing and Insulated Siding Installation |

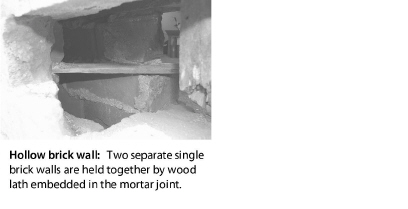

Unreinforced means that the builders used no steel or other metal reinforcement. There are three types of unreinforced brick walls.

1. Traditional brick walls with header bricks that hold two layers of stretcher bricks together. Larger buildings may have three or more brick layers instead of two.

2. Various types of hollow brick walls with usually one layer of brick on either side of an air space.

3. Wood-frame brick veneer walls with a single layer of brick veneer that is attached to a typical wood frame wall.

All three of these brick assemblies may have structural problems depending on the condition of the bricks and mortar joints. Mortar can turn to dust over the decades; hollow brick walls can be frighteningly fragile; and small movements can topple 100-year-old brick veneer. Consult a structural engineer before making any modification to an unreinforced brick building.