Chapter 2: Energy Audits and Quality Control Inspections

This chapter outlines the operational process of energy audits, work orders, and final inspections as practiced by non-profit agencies and contractors working in the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP).

WAP’s Mission

The mission of DOE WAP is “To reduce energy costs for low-income families, particularly for the elderly, people with disabilities, and children, by improving the energy efficiency of their homes while ensuring their health and safety.”

This chapter also discusses ethics, customer relations, and customer education.

Applicable DOE Policy

Comply with DOE Policy as expressed by Weatherization Program Notices (WPNs) and memorandums that DOE issues several times each program year. Also comply with the DOE’s Standard Work Specifications (SWS) for all energy conservation measure that your weatherization service provider installs. This field guide links to the SWS through a data-base tool managed by the National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL).

Why We Care about Health and Safety

The health and safety of customers must never be compromised by weatherization. Harm caused by our work would hurt our clients, ourselves, and our profession. Weatherization work can change the operation of heating and cooling systems, alter the moisture balance within the home, and reduce a home’s natural ventilation rate. Weatherization workers must take all necessary precautions to avoid harm from these changes.

2.1 Purposes of an Energy Audit

An energy audit evaluates a home’s existing condition and outlines improvements to the energy efficiency, health, safety, and durability of the home.

Depending on the level of the audit, an energy audit may include some or all of the following tasks.

• Inspect the building and its mechanical systems to gather the information necessary for decision-making.

• Evaluate the current energy consumption along with the existing condition of the building.

• Diagnose areas of energy waste, health and safety, and durability problems related to energy conservation.

• Recommend energy conservation measures (ECMs).

• Diagnose health and safety problems, and how the proposed ECMs may affect these problems.

• Predict savings expected from ECMs.

• Estimate labor and material costs for ECMs.

• Educate residents about their energy usage and proposed energy retrofits.

• Encourage behavioral changes that reduce energy waste.

• Provide written documentation of the energy audit and the recommendations offered.

2.1.1 Energy-Auditing Judgment and Ethics

The auditor’s good decisions are essential to the success of a weatherization program. Good decisions depend on judgment and ethics.

✓ Understand the policy of the DOE WAP program.

✓ Treat every client with the same high level of respect.

✓ Communicate honestly with clients, coworkers, contractors, and supervisors.

✓ Know the limits of your authority, and ask for guidance when you need it.

✓ Develop and maintain the inspection, diagnosis, and software skills necessary for WAP energy auditing.

✓ Choose ECMs according to their cost-effectiveness along with DOE and State policy, and not according to personal preference or customer preference.

✓ Don’t manipulate the energy-modeling software or a priority list to either select or avoid particular ECMs.

✓ Avoid personal bias in your influence on purchasing, hiring, and contracting.

2.1.2 Health and Safety Considerations

Energy auditors and inspectors must know and understand the health and safety (H&S) policies of the State weatherization program. H&S measures impact the budget and the economic viability of most weatherization jobs. An auditor may justify a H&S measures as any of the following types according to WPN 17-7.

1. An required H&S measure funded by the State’s H&S budget, which protects occupants or workers but isn’t justified by the energy audit and isn’t included in the average cost per unit (ACPU).

2. An incidental repair measure (IRM), with H&S benefits, funded to protect an ECM or to mitigate a relatively inexpensive hazard such as a roof leak, chimney repair, or electrical repair.

3. An H&S measure that serves as a precaution or a benefit of an cost-effective ECM, and in this case, the H&S measure adds costs to the SIR calculation.

4. A H&S benefit of an ECM that isn’t itself cost-effective but justifiable by the H&S benefits combined with the ECM’s energy savings.

When you consider whether a measure is an ECM or a H&S, evaluate its SIR, and if cost-effective, treat it as a ECM.

2.1.3 Energy-Auditing Record-keeping

The client file is the record of a weatherization job. The client file may contain all of the following items, depending on State WAP policy.

1. Customer intake document

2. Income verification

3. Owner agreement form

4. Work plan

5. Pre-inspection assessment

6. Client health-notification documents

7. Lead based paint notification form

8. Moisture and mold findings

9. Weatherization health & safety checklist

10. Energy bills

11. Manufacturer’s warranties

12. Photo documentation

13. Post-inspection report

14. EPA Lead-Safe Renovation, Repair and Painting (LSRRP) Rule, final-inspection report (if applicable)

Customer satisfaction depends on the energy auditor’s reputation, professional courtesy, and ability to communicate.

2.2.1 Communication Best Practices

Making a good first impression is important for customer relations. Friendly, honest, and straightforward communication creates an atmosphere where the auditor and clients can discuss problems and solutions openly.

Setting priorities for customer communication is important for the efficient use of your time. Auditors must communicate clearly and directly. Limit your communication with the customer to the most important energy, health, safety, and durability issues.

✓ Introduce yourself, identify your agency, and explain the purpose of your visit.

✓ Make sure that the customer understands the goals of the WAP program.

✓ Listen carefully to your client’s reports, complaints, questions, and ideas about their home’s energy efficiency.

✓ Ask questions to clarify your understanding of your client’s concerns.

✓ Before you leave, give the client a quick summary of what you found.

✓ Avoid making promises until you have time to finish the audit, produce a work order, and schedule the work.

✓ Make arrangements for additional visits by crews and contractors as appropriate.

The customer interview is an important part of the energy audit. Even if customers have little understanding of energy and buildings, they can provide useful observations that can save you time and help you choose the right ECMs.

✓ Ask the customer about comfort problems, including rooms that are too cold or too warm.

✓ Ask customers to see their energy bills if you haven’t already evaluated them.

✓ Ask customers if there is anything relevant they notice about the performance of their mechanical equipment.

✓ Ask about family health, especially respiratory problems afflicting one or more family members.

✓ Discuss space heaters, fireplaces, attached garages, and other combustion hazards.

✓ Discuss drainage issues, wet basements or crawl spaces, leaky plumbing, and pest infestations.

✓ Discuss the home’s existing condition and how the home may change after the proposed retrofits.

✓ Identify existing damage to finishes to insure that weatherization workers aren’t blamed for existing damage. Document damage with digital photos.

✓ Ask the client to sign the necessary permissions.

2.2.3 Deferral of Weatherization Services

When you find major health, safety, or durability problems in a home, sometimes it’s necessary to postpone weatherization services until those problems are solved. The problems that are cause for deferral of services include but are not limited to the following.

• Major roof leakage.

• Major foundation damage.

• Major moisture problems including mold or insect infestation.

• Major plumbing problems.

• Human or animal waste in the home.

• Major electrical problems or fire hazards.

• The home is vacant or the client is moving.

• The home is for sale.

Behavioral problems may also be a reason to defer services to a customer, including but not limited to the following.

• Illegal activity on the premises.

• Occupant’s hoarding makes difficult or impossible to perform a complete audit.

• Lack of cooperation by the customer.

Matching Funds to Avoid Deferrals

Energy auditors should assist customers in obtaining repair funds from the following sources whenever possible.

• HUD HOME Rehabilitation Funds for Homeowners

• USDA Rural Development Housing Repair Funds

• Habitat for Humanity Home Preservation

• State and local repair funds

• Church, charity, and foundation funds

Visual inspection, diagnostic testing, and numerical analysis are three types of energy auditing procedures we discuss in this section. These procedures help energy auditors to evaluate all the possible ECMs that are cost-effective according to DOE-approved energy-modeling software: Weatherization Assistant or approved equivalent. See “Quantitative Analysis: Software & Priority Lists” on page 81.

To understand the features of Weatherization Assistant, consult the DOE Weatherization Assistant training site.

The energy audit must also propose solutions to health and safety problems related to the energy conservation measures.

Visual inspection orients the energy auditor to the physical realities of the home and home site. Among the areas of inspection are these.

• Health and safety issues

• Building air leakage

• Building insulation and thermal resistance

• Heating and cooling systems

• Ventilation fans and operable windows

• Baseload energy uses

• The home’s physical dimensions: area and volume

Measurement instruments provide important information about a building’s unknowns, such as air leakage and combustion efficiency. Use these diagnostic tests as appropriate during the energy audit.

• Blower door testing: A variety of procedures using a blower door to evaluate the airtightness of a home and parts of its air barrier.

• Duct leakage testing: A variety of tests using a blower door and pressure pan to locate duct leaks.

• Ventilation testing: Measure airflow through existing exhaust fans with an exhaust-fan flow meter.

• Combustion safety and efficiency testing: Sample combustion by-products and measure depressurization to evaluate safety and efficiency. Test for existing gas leaks. Test the home’s ambient air for CO.

• Test for fuel leaks with a combustible gas detector.

• Infrared scanning: View building components through an infrared scanner to observe differences in the temperature of building components inside building cavities.

• Appliance consumption testing: Monitor refrigerators with a logging watt-hour meter to measure electricity consumption.

2.3.3 Quantitative Analysis: Software & Priority Lists

Energy auditors currently use Weatherization Assistant (WA) to determine which ECMs have the highest Savings-to-Investment Ratio (SIR). The ECMs with the highest SIRs are at the top of the WA priority list for a particular home.

SIR = Lifetime savings ÷ Initial investment

DOE WAP and the State WAP program require that ECMs have an SIR greater than 1. Subgrantees must install ECMs with higher SIRs before or instead of ECMs with lower SIRs.

The auditor must collect information to make informed decisions about which ECMs to choose.

✓ Measure the home’s exterior horizontal dimensions, wall height, floor area, volume, and area of windows and doors.

✓ Measure the current insulation levels.

✓ Do a test to evaluate air leakage and duct leakage.

✓ Do a combustion efficiency test to evaluate the heating system’s efficiency.

✓ Evaluate energy bills and adjust the job’s budget within limits to reflect the potential energy savings.

The work order is a list of materials and tasks that are recommended as a result of an energy audit. Consider these steps in developing the work order.

✓ Evaluate which ECMs have an acceptable savings-to-investment ratio (SIR) using the energy-modeling software.

✓ Select the most important health and safety problems to correct based on what problems are directly related to the cost-effective ECMs.

✓ Provide detailed ECM specifications so that crews or contractors clearly understand the materials and procedures necessary to complete the job.

✓ Estimate the cost of the materials and labor.

✓ Verify that the materials needed are in stock at the agency or a vendor.

✓ Inform crews or contractors of any hazards, pending repairs, and important procedures related to their part of the work order.

✓ Obtain required permits from the local building jurisdiction, if necessary.

✓ Specify interim testing during air-sealing and heating-system maintenance to provide feedback for workers.

✓ Consider scheduling an in-progress inspection during an important retrofit.

✓ Consider scheduling a final inspection for the job’s final day if possible to involve the workers in the inspection

2.5 Quality Control Inspections

The quality-control inspector (QCI) is responsible for the quality control and quality assurance of the weatherization process. The Building Performance institute (BPI) certifies QCIs to perform Subgrantee job inspections and Grantee (State) monitoring.

Grantees must follow DOE’s QCI Policy or else submit their own QCI Policy for approval by DOE. Good inspections provide quality control for both work orders and energy audits. There are two common opportunities for inspections: in-progress inspections and final inspections.

DOE encourages QCIs to inspect jobs while the job is in progress. In-progress inspections evaluate worker safety, observe ongoing procedures, and provide training, technical assistance, and occupant education.

See “Occupant Education about Alarms” on page 27.

These measures are good candidates for in-progress inspections because of the difficulty of evaluating them after completion.

• Dense-pack wall insulation

• Attic air sealing

• Insulating closed roof cavities

• Furnace installation or tune-up

• Air-conditioning service

• Duct testing and sealing

• Lead-safe work practices

Rural in-progress inspections may require too much expensive travel and time, making in-progress inspections impractical except for the final inspections.

2.5.2 Subgrantee Final Inspections

The weatherization service provider or Subgrantee does final inspections on all of its weatherized homes for quality control. Quality control is a term for the in-house self-evaluation of weatherization jobs. A certified QCI completes a final inspection before the Subgrantee reports a weatherization job as a completion to the Grantee.

If the QCI is a different person from the energy auditor, the Grantee must perform independent reviews of 5% of DOE WAP units completed by the Subgrantee.

If the QCI is the same as from the energy auditor, the Grantee must perform independent reviews of 10% of DOE WAP units, completed by the Subgrantee. The Grantee must also develop a quality assurance plan that ensures that the individual who is functioning as both the auditor and the QCI is able to consistently perform both tasks.

Final inspections ensure that energy auditor identified the right ECMs, and that the crew and contractors installed the ECMs as specified in the work order.

Energy-Audit Quality Control

While the work order is the more obvious priority of the inspection, quality control for the energy audit is nearly as important. Answer these questions during a final inspection.

• Did the auditor find all the ECM opportunities?

• Did the auditor identify all the health and safety concerns and worker safety hazards?

• Do the audit’s ECMs comply with the computer analysis or priority list?

Work-Order Quality Control

If you complete the final inspection with the crew or contractor on site, you can help workers to correct deficiencies without their returning to the home later. Ask these questions during your inspections.

• Did the energy audit find the best combination of ECMs for the home?

• Did the work order adequately specify the labor and materials required by the energy audit?

• Did the crew follow the work order?

• What changes did the crew leader make to the work order? Were these changes appropriate?

• Is the completed weatherization job, the energy audit, and the work order aligned with State policy, DOE policy, and the SWS?

Verify the following during the final QC inspection.

✓ Confirm that the crew installed the approved materials in a safe, effective, and neat way.

✓ Confirm that the crew matched existing finish materials for measure installation and necessary repairs.

✓ Review all completed work with the client. Confirm that the client is satisfied.

✓ Verify that combustion appliances operate safely. Do worst-case draft tests and CO tests as needed.

✓ Do a final blower door test with simple pressure diagnostics if appropriate.

✓ Use an infrared scanner, if available, to inspect insulation and air-sealing effectiveness.

✓ Specify corrective actions whenever the work doesn’t meet standards.

✓ Verify that the crew used the correct lead-safe procedures if these procedures were necessary in installing ECMs.

✓ Verify that all required paperwork, with required signatures is in the client file. See “Energy-Auditing Record-keeping” on page 76.

2.6 Grantee (State) Monitoring of Subgrantees

Quality control is an internal process of a weatherization service provider (Subgrantee) focusing on the final inspection. Quality assurance is a third-party inspection performed by a monitor employed by either the Grantee or a third party, working for the State.

Certified quality-control inspectors (QCIs) may perform quality-assurance inspections. The following are important elements of these inspections.

• Verify alignment among energy audit, work order, and final inspection.

• Report findings, concerns, and issues, and specify corrective action.

• Resolve any existing findings, concerns, and issues.

• Provide feedback on material quality and worker performance, both good and bad.

• Survey clients for level of satisfaction.

• Review the paperwork for completion and compliance.

2.6.1 DOE Monitoring of Grantees (States)

The DOE monitors the Grantees based on their State Plan and associated Health & Safety Plan, required for annual WAP funding application. The DOE Project Officer’s (PO’s) job is similar to the agency’s QCI. However, the PO is a DOE employee and reports his or her monitoring results to the State Grantee and the DOE but not the Subgrantee. DOE monitoring is more administrative and less technical. The PO need not be a certified QCI.

POs interact with Grantees in these ways.

1. Advise Grantee how to continue to meet WAP program requirements.

2. Resolve outstanding findings, concerns, and issues.

3. Identify training and technical assistance needs.

4. Document strengths or and weaknesses of the State program.

5. Document best practices for distribution to the WAP network, if appropriate.

The monitor issues a report and the Grantee must respond in writing. Major findings require the Grantee to tell the DOE how the Grantee plans to correct the problems and pay for the corrections.

2.7 Understanding Energy Usage

A major purpose of any energy audit is to determine where energy waste occurs. With this information in hand, the energy auditor then allocates resources according to the energy-savings potential of each energy-conservation measure. A solid understanding of how homes use energy should guide the decision-making process.

|

Energy User |

Annual kWh |

Annual Therms |

|---|---|---|

|

Heating |

2000–10,000 |

200–1100 |

|

Cooling |

600–7000 |

n/a |

|

Water Heating |

2000–7000 |

150–450 |

|

Refrigerator |

500–2500 |

n/a |

|

Lighting |

500–2000 |

n/a |

|

Clothes Dryer |

500–1500 |

n/a |

|

Estimates by the authors from a variety of sources. |

||

2.7.1 Baseload Versus Seasonal Use

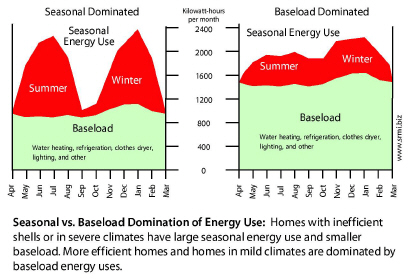

We divide home energy usage into two categories: baseload and seasonal. Baseload includes water heating, lighting, refrigerator, and other appliances used year round. Seasonal energy use includes heating and cooling. You should understand which of the two is dominant as well as which types of baseloads and seasonal loads are the highest energy consumers.

Many homes are supplied with both electricity and at least one source of combustion fuel. Electricity can provide all seasonal and baseload energy, however most often there is a combination of electricity and natural gas, oil, or propane. The auditor must understand whether loads like the heating system, clothes dryer, water heater, and kitchen range are serviced by electricity or by fossil fuel.

Total energy use relates directly to potential energy savings. The greatest savings are possible in homes with highest initial consumption. Avoid getting too focused on a single energy-waste category. Consider all the individual energy users that offer measurable energy savings.

Separating Baseload and Seasonal Energy Uses

To separate baseload from seasonal energy consumption for a home with monthly gas and electric billing, do these steps.

1. Get the energy billing for one full year. If the customer can’t produce these bills, they can usually request a summary from their utility company.

2. Add the 3 lowest bills together.

3. Divide that total by 3.

4. Multiply this three-month low-bill average by 12. This is the approximate annual baseload energy cost.

5. Total all 12 monthly billings.

6. Subtract the annual baseload cost from the total billings. This remainder is the space heating and cooling cost.

7. Heating is separated from cooling by looking at the months where the energy is used — summer for cooling, winter for heating.

8. For cold climates, add 5 to 15 percent to the baseload energy before subtracting it from the total to account for more hot water and lighting being used during the winter months.

Energy indexes are useful for comparing homes and characterizing their energy efficiency. They are used to measure the opportunity for application of weatherization or home performance work.

Most indexes are based on the square footage of conditioned floor space. The simplest indexes divide a home’s energy use in either kilowatt-hours or British thermal units (BTUs) by the square footage of floor space.

A more complex index compares heating energy use with the climate’s severity. BTUs of heating energy are divided by both square feet and heating degree days to calculate this index.

Customer education is a potent energy conservation measure. A well-designed education program engages customers in household energy management and assures the success of installed energy conservation measures (ECMs).